Designing the ISA and the simulator is fine and dandy but it does not beat running a custom CPU on real hardware. Unfortunately, I don't have tens of thousands of euros to make a custom chip. The best I can do is to run it on an FPGA. An FPGA is a chip with a lot of logic gates that can be wired together to make any logic circuit. And our CPU is a logic circuit.

What we need to do is to use a hardware description language such as Verilog or VHDL to describe the CPU. I choose to use Verilog as I prefer its more concise syntax but both languages can do the same things in a very similar manner.

I designed my CPU in 4 main blocks:

The CPU is nice to have but it cannot do much on its own. It needs peripherals to interact with the outside world. The one we will use the most is the UART, a peripheral used to send and receive serial messages, such as our beloved "Hello, world!"

The peripherals are put on the memory bus of the CPU so that they can be interacted with. There is also the RAM and the ROM of the processor on that bus.

The peripherals are controlled by writing and reading at special memory addresses, in a way similar to the simulator. For example, the addresses used to interact with the UART are between 0xFF16 and 0xFF19. Here is the code used to do so, notice how similar it is to the code that ran on the simulator:

@align_word

label string

@string Hello, world!

@rawbytes D A 0

label start

set 15

cpy R3 ; Length of the message to print in R3

setlab string

cpy R2 ; Pointer to the character to print in R2

label print-loop

; Loading a character from R2 and storing it in R3

tbm

load R2

cpy R1

tbm

; Function call made thanks to the `callf` macro

callf printc

; Incrementing the pointer to the desired character

set 1

add R2

cpy R2

; Decrementing the number of characters left to print

set 1

sub R3

cc2

cpy R3

; If the number of characters left to print is not 0, jump back to the start of the loop

set 0

eq R3

cmpnot

setlab print-loop

jif

quit

label printc

pushr R2 ;addrs

pushr R4 ;waiting loop pointer

set+ 0xFF16 ;UART tx_cmd addr

tbm

cpy R2

setlab printcLoop

cpy R4

label printcLoop

load R2 ;testing that R2 is not 0 to see if we are ready to print

cpy R12

set 0

eq R12

read R4 ;until ready, go back

jif

set 1 ;computing the data addr

add R2

cpy R12

read R1 ;writing the char

str R12

set 0 ;sending command

str R2

tbm

popr R4 ;restoring registers

popr R2

ret

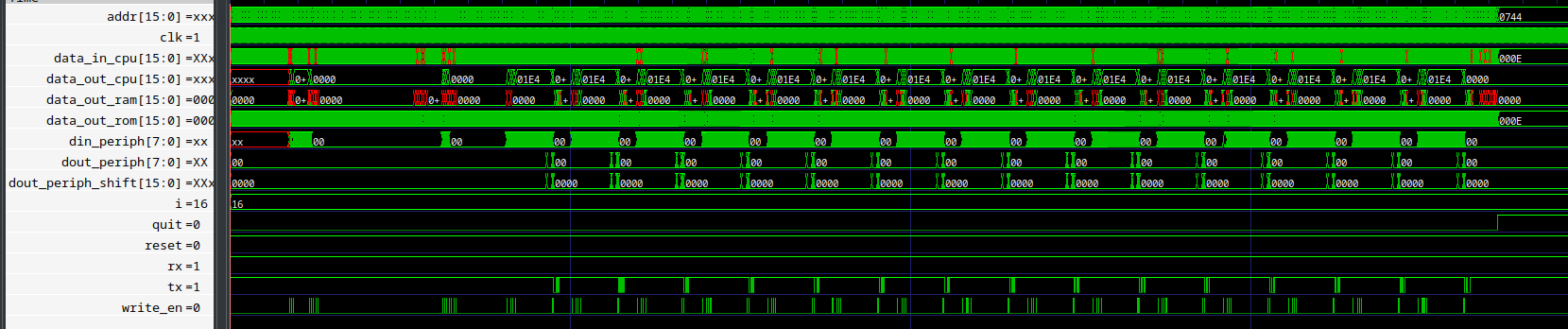

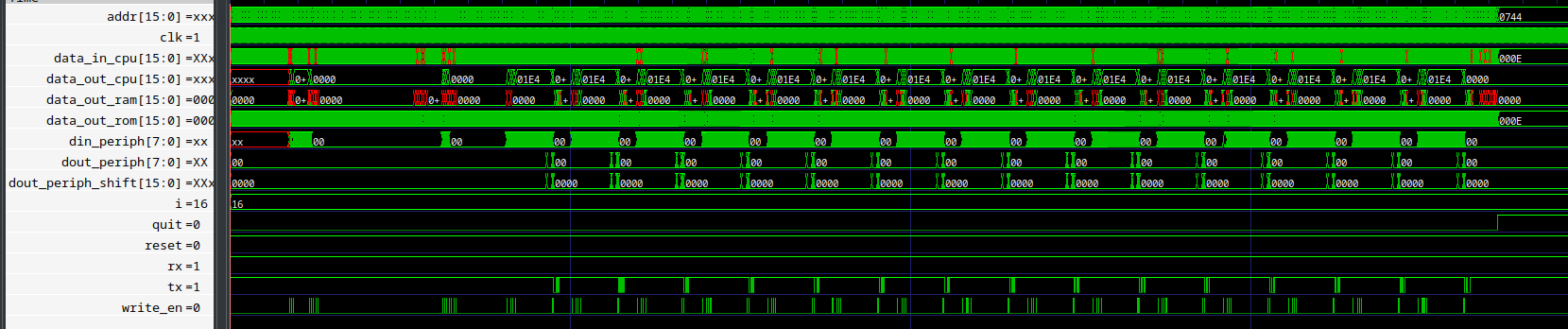

To ensure that everything works well, it is important to test the CPU, its code, and its peripherals. For example, here is the result of the simulation that sends "Hello, world!" over a UART TX line.

Note how the TX line moves a bit each time a character is sent.

Once the Verilog code is ready, we must synthesize it to convert it into a bitstream that can be loaded into the FPGA. Here comes the not-fun part: "Slack not met".

If a signal goes through too many logic gates between two registers, the signal does not have the time to be fully updated before reaching the end register. This causes the design implemented in the FPGA to have a different behavior than what has been described in Verilog. Thankfully, the FPGA design tools (Vivado in my case) can alert us if such a problem arises and it is up to the designer to fix the issue.

The issue can be fixed by putting intermediate registers in the signal paths that cause issues. This increases latency but this is a small price to pay to have a working design. Once the issues are ironed out, the design can be downloaded to the FPGA.

We are now able to have our hardware design in the FPGA, but how can we give it software to run? The first solution is to bake the software as a ROM in the MCU design. This is very easy to do but this has a major drawback, to put a new software, we must restart the synthesis process, which is lengthy.

A better solution is to embed a bootloader in the MCU that can read firmware given over the UART link and put it into memory. That way, new software can effortlessly be downloaded.

The bootloader is a normal program that I write into a ROM in the MCU. It is executed on boot and uses the peripherals (UART and timers) to get the desired software from an outside source and write it into RAM from which it will be executed. Once the software is fully loaded, the bootloader resets the MCU's state and jumps into the new software.

Here is a small clip of me uploading the "Hello, world!" program to the processor and its reply.

Sending a "Hello, world!" over a UART link is a nice step, but it would be even better to write it onto a screen. To do so, we will need to design a basic GPU to pair with our CPU.